7/4/2020 — Concord, Massachusetts

Tuesday, March 17th 2020. 6pm. An emergency alert shook my phone. I was running down the highway in lower Manhattan, hobbled by a backpack strapped to my shoulders, a heavy briefcase and travel bag in each hand. They held two weeks of clothing, a siddur and chumash — Hebrew prayer book and Bible, a laptop and enough condoms to depopulate a small city. (They remain untouched as of this writing.) I dropped a bag to get my phone. Huge letters shouted: COVID-19 ALERT! It was all the confirmation I needed. Go.

Leapt up the stairs of my parking garage, throttled the Sapphire Dragon along the banks of the Hudson River. Welled a tearless sob when I passed my brother’s house off the Henry Hudson Parkway. Normally I’d pull over to see him and his sweet wife, their one, then two, now four children. Each one as startling and miraculous as an anemone flower.

His misphocha, family, were my northern destination. They were the point of a quick journey. I kept slicing north and then east, across empty highways that hazed in Westchester and went dark in Connecticut. I hit pause at a restaurant but it was closed. The world had chained the doors, shut the lights. Back on the highway. Hartford flew past. Sixth gear hollered all the way to Massachusetts.

Imagine running as hard and fast as you can from a threat. Doesn’t matter where you go, just away, fast. Each stretch of legs compels you forward. You chug arms and push so hard you almost fly off the ground. Your lungs burst in flame. Fear transforms to trajectory and then — finger snap!

The road vanishes.

You are holding a cold beer while your best friend laughs and his dog beckons for a toss of a softball.

A gravity wagon full of grain shelters a second border collie. Geese glide northeast to Canada — unperturbed, on mission. Wings rhythmically clap to a song so old it predates each one of your ancestors, going back to your one hundredth grandparent, to their 10,000th grandparent, to their 100,000th grandparent, to long before we were ever a species.

Cities and phone notifications and strip malls blot out the song but it plays loudly at the farm. You can hear it as you drink your beer, even in the cold late winter of cover crop and unplowed fields. You can’t read the music or tell one movement from the next, but the organic grower next to you, your oldest friend, he strums callused fingers to all the right chords. Both of you head to the farm house. The collies trot after.

You are safe.

Pink Floyd recorded their ninth album, Wish You Were Here, at Abbey Roads Studios in 1975.

A few years later, my mom took my hand and walked us up our quiet side street in the Newton suburbs. She carefully crossed double-lane Grant Street, rang the bell at a house on the Montvale Crescent hill. Jan Rodgers, in her early 30s like my mother Alexandra, answered the door.

“I hear you’re new to the neighborhood and have a boy Zachary’s age,” Alexandra said.

“Why yes I do. Here he is.”

Andrew appeared with his blond bowl haircut. I was smaller, with chestnut hair. We ran off to play in the yard. 1977.

Yesterday I directed him as he backed up a livestock trailer to a patch of forest by the pigs. A few moments later we set up irrigation for a field of emerging strawberries. If child’s play is practice work, then not much has changed in 43 years, we’re still enjoying each other’s company outside — except now he’s a father of two and my hair has turned more ash than coal.

The eponymous middle song of Pink Floyd’s 1975 album is a bluesy, forlorn lament. It tastes like you’re no longer in love. It’s gone.

The only thing you can do, the only homage you can offer the memory, is to rotate the sharped-edge regret in your mind as each turn tears the tender places within you. It should have been this, but it was always that. I wanted right side up, it was always upside down.

After a melancholy guitar strum, the song’s opening message reads bitter and accusatory.

So, so you think you can tell

Heaven from hell

Blue skies from pain

Can you tell a green field

From a cold steel rail?

A smile from a veil?

Do you think you can tell?

But a weariness in Roger Water’s voice restrains the criticism. It’s more dolorous than angry. If you listen to the song a few more times you sense introspection and self examination. Invert the pronouns and you’ll see what I mean. The “you” becomes “I.”

I think I can tell, heaven from hell? Blue skies from pain?

The lyrics become an admission of failure to understand anything at all. “I” amplifies the loneliness and regret.

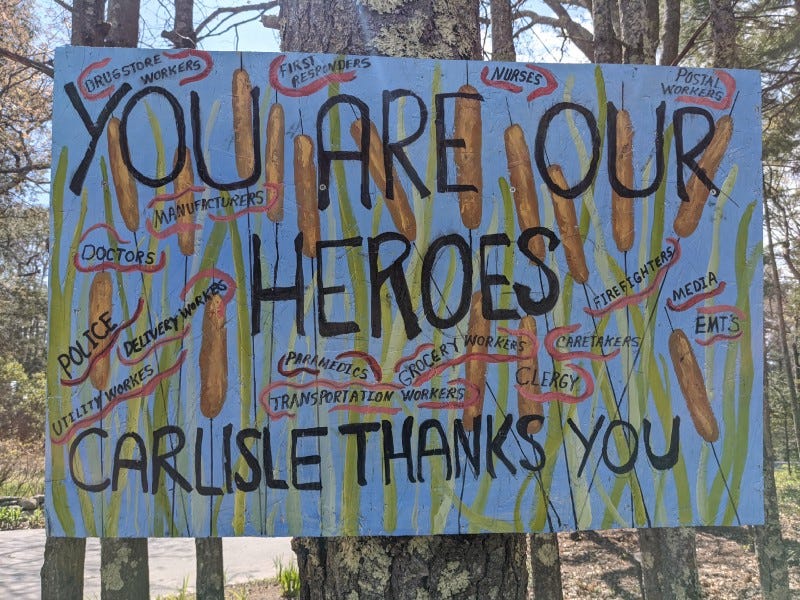

This is what I sensed but didn’t fully understand when the song came on the radio when I drove through Carlisle last week. What was this song about? What were all those sad questions? I went back to my hut, my in-law shack, my Airbnb with plaid curtains and four leather sofas from the 1980s to listen again.

Back in the 1980s as a teenager I didn’t listen to lyrics closely. Pink Floyd, along with Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers Brand, The Rolling Stones, Rush, Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Who were bequeathed to us by neighborhood boys with older sibling or uncles with Trans-Ams. What a handful of musicians recorded in London in 1975 would take a good fifteen years to arrive to the Boston suburbs of my cohort. We would receive the transmissions passively yet faithfully. Playing the albums over and over again. At the time we just thought if as music, eventually people would call it Classic Rock.

Now I think it’s safe to ask, and what I had an inkling of when my tastes changed to artier, edgier music, it’s Classic for whom? It was all white, corporate-sponsored music coopted from original Black artists who were robbed of royalties and promotion. Parliament or Funkadelic or Muddy Waters never played in my profoundly segregated suburbs.

We grew up listening to a catalog of music we never asked for, it was handed to us with the solemn ineluctability of tradition, commanded to us in utterances whose instructions only varied by the nouns as the decades ticked by: “spin this record” “put this in your Walkman” “play this CD.”

Pink Floyd had a seat at the table. They weren’t at the head, that was for Led Zeppelin, but they were close, and since they were so prolific, there was always more to hear.

The other day Andrew and I weeded peas as they wended their slow trajectory up trellises in Field 1B. I grabbed plants with my hands while he pulled a thinning hoe. Working at Andrew’s farm feels like being a six-year-old who, much to his surprise, has to fly a Boeing 747 to Heathrow. For the past three-and-a-half months, and for all the weekend visits before now, I keep finding myself asking him endless child’s questions: “what does this do?” “why does this happen?” “how does this work?” “where does this go?”

Ext. OUTSIDE THE GREENHOUSE — DAY

ZACHARY pulls up in a tractor. He parks it perfectly by a huge implement. He has a small, smug smile. He’s got this.

CLOSE UP on his hand as he shuts off the tractor.

He turns what looks exactly like a car key. Nothing happens.

He turns it again. Nothing happens.

He turns it again… Nothing.

ZACHARY examines a thicket of levers and knobs by the tractor seat. None are marked, but he knows they don’t shut off the engine.

He looks around the farm. There are trays bursting with plants. FARM HANDS go here and there. Work needs to be done. He’s stuck on a tractor.

He takes out his phone. His smile is gone.

CUT TO:

INT. WASH UP ROOM — DAY

A 30s woman, red hair under a baseball cap, MARY LIZ, talks to her INFANT BOY perched in plastic bin. She washes thousands of carrots. She watches her son, works with both hands and talks to MEREDITH, who looks like an Israeli commando in farm clothes.

MARY LIZ’S phone RINGS. Despite being busier than anyone ever, she answers. She’s that kind of person.

ZACHARY: Hey, umm, ahh… Know how to turn off the high crop?

MARY LIZ: Yeah, Lift up the accelerator handle all the way. It’ll shut off. Why?

ZACHARY: Just asking.

As Andrew and I weeded and talked I examined the bed. A stalk rose from soil. On it, just off the ground, a small double leaf grew. It had a different shape yet the same color and texture of the pea leaves further up. These are the things your mind detects when weeding. If it’s different shape/size/color, pull it and toss. Be sure NOT to do that to the crop. You keep those.

This small double leaf hovering over the soil stood out. Above it larger, correctly shaped leaves lounged off the plant like they were on vacation, just soaking in the rays man, just loving the sun dude.

But that lower leaf. The child asks a question.

“That’s a cotyledon,” Andrew explained. “It’s the first leaf of a germinated seed.”

“OK yeah. Caughty-lee-dun. Got it.” Not really.

By the middle of Wish You Were Here the song goes to a deeper place, it’s more about behavior and thoughts than perception.

Did they get you to trade

Your heroes for ghosts?

Hot ashes for trees?

Hot air for a cool breeze?

Cold comfort for change?

Did you exchange

A walk on part in the war

For a lead role in a cage?

I had escaped my cage in Manhattan and was now a walk on part in — not a war exactly — but in the frenzied, tedious, impossible, unending, exhausting, back wrenching, sweat inducing campaign of marshaling food from the earth.

It turns out, as some of you must already know, that Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” isn’t about two lovers separated by bad decisions and regret. It’s about two close friends riven by crisis and conflict. Roger Waters wrote it as an ode to his childhood friend, Syd Barrett, with whom he had formed the group ten years earlier. After their first band name was taken, it was Barrett who had re-named them after genius American bluesmen Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. (Cf. cooptation and exploitation.) Barrett had written their first four hit songs. Barrett and Waters both sang and played guitar.

Barrett & Waters were Pink & Floyd.

And then… they weren’t.

In his late 20s Barrett fell victim to profound mental illness and way too much LSD. He couldn’t function in the rapidly rising band any longer. The parallels between Andrew and me, and Waters and Barrett, end well before their epic breakup.

Our friendship is ancient but uncomplicated. And let’s be serious, Andrew would never hire me as his business partner. I’m way too slow at transplanting and every other farm task imaginable, and the last time I took psychedelics was… never mind. Long ago.

How I wish, how I wish you were here

We’re just two lost souls

Swimming in a fish bowl

Year after year

Running over the same old ground

And how we found

The same old fears

Wish you were here

I’m ruminating on this friendship and the succor of the farm and the music of our youth because, when I publish this essay, I will no longer be in a semi-crappy Airbnb near Clark Farm in Carlisle, Massachusetts. I will be in a farm house in northern Vermont, looking backwards, missing my oldest, closest friend.

In Judaism we learn that paradox is the key to understanding. It’s one of our best analytic methods and liturgical tropes. “God is one yet God will be one” as the Aleinu prayer insists. Moses was our leader but also, unchosen. In an episode in the desert, an enemy priest starts to curse Israel but instead blesses us.

Creating inversions teaches you more than Torah, it reveals meaning in art and existence. Take life and turn it upside down. Now turn yourself upside down. How do you see it now? How do you feel, now?

In other words, this is a long way of saying that Wish You Were Here could just as easily be, Wish I Was There.

If my cotyledon leaves are just soaking in the rays man.

If I’m forming a new life after being caged in an apartment in a city that blots out nature’s music.

If my first leaves are delivering nutrients and carbohydrates for further growth, if I am slowly wending my way upwards to a new trajectory, then I have really only have one person to thank.

For 111 days Andrew Rodgers showed me a hospitality that is a sukkah in the fields. A temporary shelter in the wilderness that speaks to both fragility and endurance — another small paradox.

There are the supporting cast members to thank: Meredith Pierce (and her family), Mary Liz (and her baby Graham), the camaraderie of Jesus and Franny, teenagers Anson and Phoebe, the wider Carlisle community of Kirsty, Chris, Eleah, Matt and even snarky teenage Cam, the farm crew college kids who swap jokes and pretend to listen to my academic advice in the fields.

Most of all there’s Farmer Andrew who built this small village. Who never tires of telling me, yet again, and even again, how to operate a high crop, sucker a tomato, work a stirrup hoe, hitch a trailer and much more information than I will ever retain. Thanks buddy.